Seeing Through the Clouds

What the PC, mobile and cloud-computing booms tell us about the future of AI.

As we head into 2024, it’s clear that generative AI remains the biggest trend in tech. ChatGPT racked up 100 million users in two months, while tech giants Amazon and Microsoft are focusing their product roadmaps—and their recent user conferences—squarely on AI. And the boardroom drama at high-profile startup OpenAI provided an early Christmas present for Silicon Valley journalists looking for juicy scoops.

But while many of generative AI’s capabilities are legitimately new, I believe the development of the technology also mirrors, in many ways, the rise of previous disruptive technologies. These include the PC boom of the 1980s and 90s, the rise of mobile apps after the launch of the iPhone and the cloud-computing revolution of the last decade.

So, what do these previous tech waves have to tell us about the AI future—including which business models will win out and what investors should be looking for as they evaluate the new AI landscape? Here are five key takeaways.

Commercially minded entities have a much higher success rate and cleaner path to drive big technological shifts.

This issue was highlighted recently by the recent management/board shakeup at OpenAI, a company founded as a nonprofit but one that later added a commercially focused subsidiary. This structure, in my view, likely contributed to its recent instability and might provide an opening for some of its competitors to grab early market share.

Looking back, it’s clear that big, commercial endeavors to push through new technologies—including the “Wintel” partnership between Microsoft and Intel that fueled the PC boom, and Apple’s investment in the iPhone ecosystem that drove the mobile-app revolution—are important to getting new tech to stick. Similarly, the cloud-computing era didn’t truly kick off until Amazon started leasing out its unused computing infrastructure as a side business; now, that Amazon Web Services unit just reported an astounding $23 billion in quarterly revenue. By contrast, an earlier community project in cloud-computing called OpenStack, backed by a non-profit foundation, launched in 2010 but never got as much traction.

OpenAI, similarly, started as an experiment for the greater good of advancing human intelligence. But I don’t think it was until Microsoft funded the company’s commercial efforts with billions of dollars and other resources that the company’s groundbreaking ChatGPT application became a reality and captured the public’s imagination. I think broadly, developers and founders need a commercially focused foundation they can bank on to realize their product visions, and this is certainly true of generative AI.

Competition is usually required to drive real market adoption of a new technology.

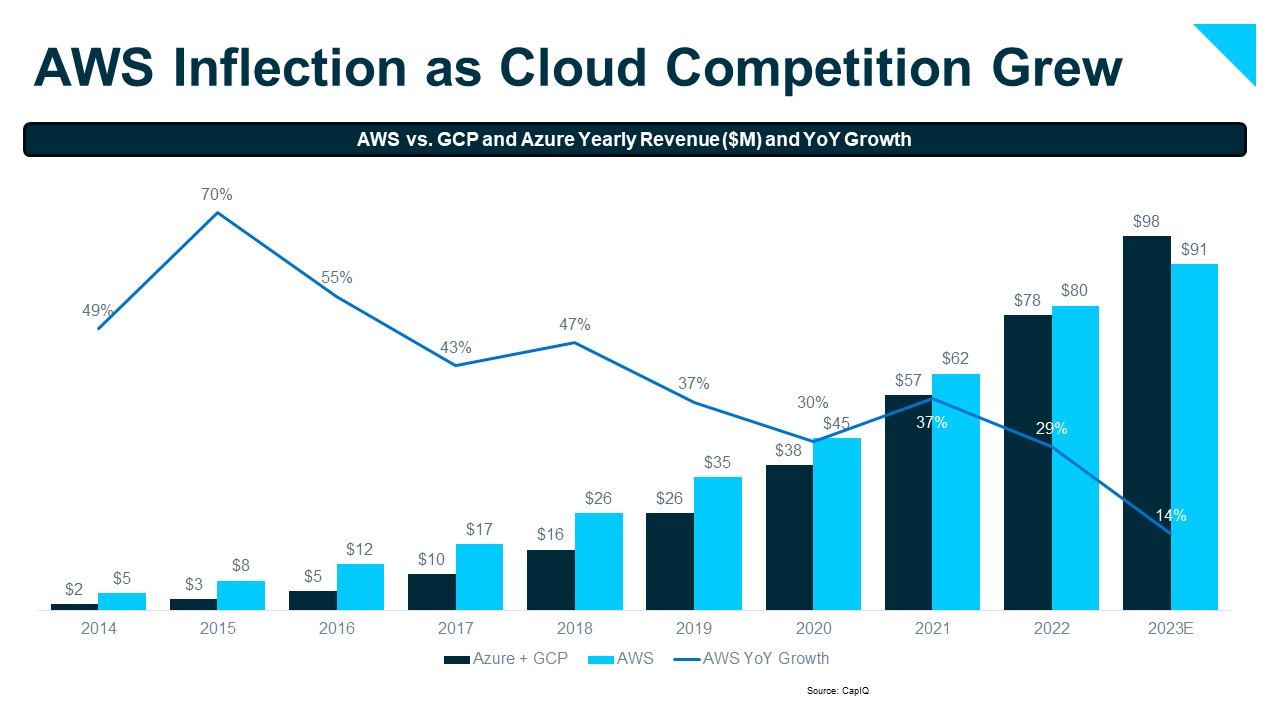

AWS launched its cloud service in 2007 and saw it grow nicely for a few years. But it wasn’t until Microsoft and Google really started investing in their own cloud services five to seven years ago (see chart below) that the market began to explode. Based on our research, most technology buyers don’t like being beholden to one vendor for a critical technology (Wintel, even Nvidia for AI chips today) and usually take a cautious stance during the early stages of a tech cycle. Who wants to be locked in?

Competition from credible firms comforts the mass market. Similarly, with generative AI, many big players are now jockeying for position and offering credible products, which I think is a good sign for the market. Microsoft has allied with ChatGPT maker OpenAI, while AWS has focused, among other initiatives, on its new Bedrock AI product, which was made generally available in September. Google, which introduced a new, neural-network architecture called Transformer in a seminal paper in 2017, has been surprisingly late to the party, but the company’s recent announcements about AI models such as Gemini and PaLM 2 also make it a credible, albeit late, entrant to the mix.

Creating new standards early in a new tech cycle can create competitive moats.

A few decades ago, Intel and Microsoft formed a partnership through which Intel’s chips ran popular PCs powered by Microsoft’s Windows operating system—which left Apple out of the PC game early on. In the Internet era, similarly, Intel employed legions of software engineers to optimize the company’s hardware for corporate software made by companies like VMware, RedHat and Oracle, creating a “standard stack” upon which to write enterprise-software applications and middleware.

In the current, generative-AI era, chip maker Nvidia has created a moat with its CUDA platform, which optimizes the company’s GPU chips for popular AI models—made by OpenAI, Anthropic, Cohere, etc.–and keeps AMD, Intel and others at bay. Competitors can build competing chips to run AI apps, but building the optimization layer for state-of-the- art AI models will take years for new players to replicate.

Vertical integration can disrupt the standardized stack.

When Windows standardized on Intel chips to create the Wintel market standard, Apple had to follow along as well by using Intel silicon for its Macintosh systems. But following the company’s breakout hit with the iPhone, Apple integrated vertically and built its own chip for phones to disrupt Intel’s market dominance. It wasn’t the most powerful chip, but mobile phones primarily needed better power management, and Apple was able to focus on that functionality.

Today, in the AI market, Nvidia GPUs may represent the most powerful silicon available. But I wouldn’t be surprised if Microsoft and OpenAI go downstream themselves and produce new chips purpose-built for their own AI models. Amazon Bedrock could potentially standardize on Trainium and Inferentia silicon, rather than Nvidia GPU instances, for its mass-market models as well. Nvidia, in anticipation, is building its own models, and vertical integration may re-shape how the mega vendors compete in the lucrative gen AI field. (Though I’m not sure our current FTC will allow too many big mergers in this space in the near future, given the tighter antitrust environment.)

In a new tech wave, the bulk of the value happens at the application and middleware layer.

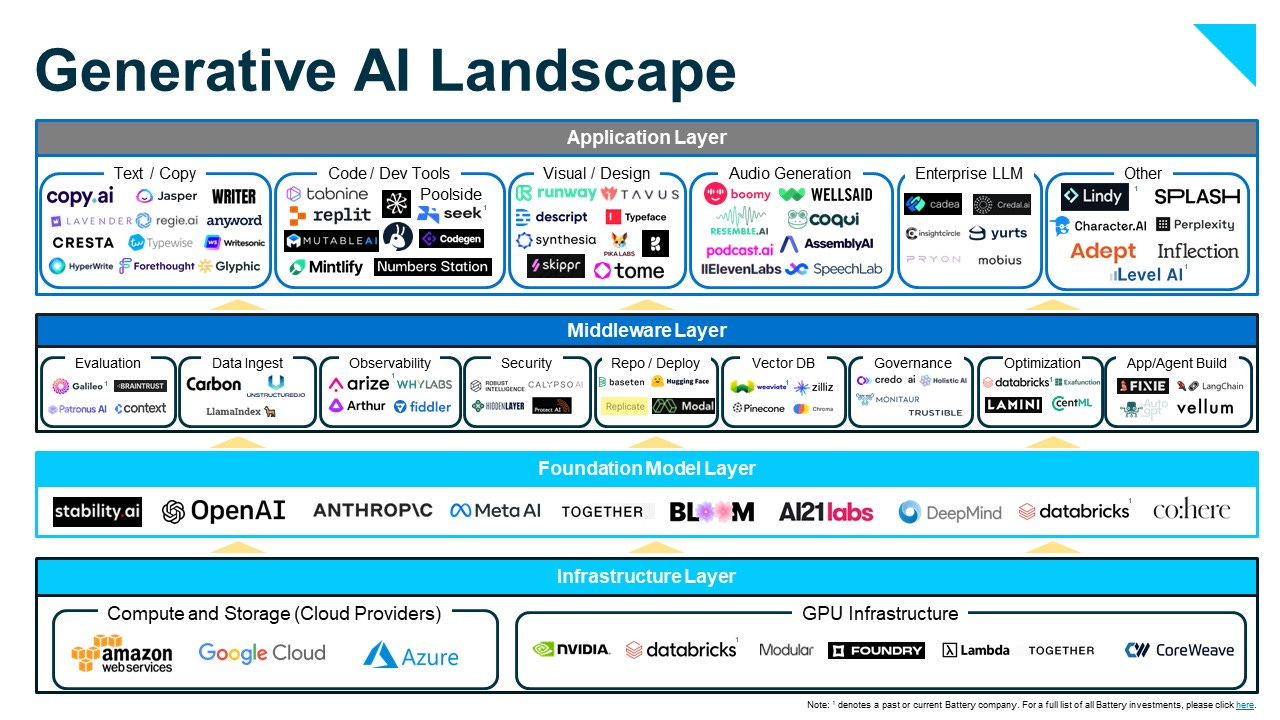

Foundational models and chips are critical to getting AI off the ground, but this infrastructure is expensive, requiring billions of dollars to commercialize a product (see: OpenAI and ChatGPT). In my mind, this is not a game for venture-backed startups. Sure, there are promising, high-level AI model alternatives like Anthropic, Cohere and Mistral. But these companies are mostly funded by larger tech companies with a strategic interest in the technology. They resemble Intel’s investments in RedHat or VMware, and in my mind don’t represent a venture model. Below is a graphic representation of the generative-AI landscape that we presented last month at our OpenCloud conference.

I think history shows us that with AI, as well, value will accrue in the application layer; companies will use workflow and delightful experiences as offense to engage hundreds of users, all while leveraging their “data moat” as defense. In the Internet era, it wasn’t the Internet-infrastructure, or fiber-optic cable companies, that emerged as the big winners. Instead, it was Amazon, with its hugely popular shopping site, Facebook and Instagram with their viral consumer services, etc. that benefited and grew into hugely valuable companies.

The same thing happened with cloud computing as multiple clouds made best-in- class middleware solutions — think databases, observability tools, security — more prominent. As AI develops, I think there will be a set of new companies—think of them arms merchants—that will allow customers to build valuable generative-AI apps. Just like MongoDB, Datadog, Snowflake, Databricks* and others benefited as best-in-class, multi-cloud providers in the cloud-middleware market, I also expect to see the development of next-generation vector databases, model-observability companies and new compliance solutions, among others.

We may see a shakeup in how the “big three” cloud providers make out in the new AI market.

Right now, despite recent progress by Microsoft and, to a lesser extent Google, AWS still rules in the cloud-computing market in terms of market share. Interestingly, though, I think this dynamic will shift in the nascent AI market. Microsoft Azure, thanks to its GitHub acquisition and, more recently, its prominent partnership with OpenAI, in my mind has very high developer mindshare when it comes to developing and testing AI models.

Interestingly, Microsoft has gone the vertical-integration route that Apple adopted in the mobile era to, ironically, fight back against Microsoft. AWS, by contrast, seems to be coming from behind and is making multiple AI announcements to gain mindshare as it scrambles to catch up. Google is in the hunt, too, focused on commercializing its early research and competing with AWS for the runner-up spot. The jury is still out on whether the company can execute as well as Azure did as a distant second in the previous race for cloud-computing market share. Data clouds like Databricks’ and Snowflake’s could also become competitors to the Big Three, providing the best experience to build and run AI models.

When it comes to AI, I think the past is prologue. Generative AI has the potential to be just as, or more, important than past technology waves like PCs and cloud computing as it pushes computers to automate tasks that usually require human intelligence — and changes our world as a result. I think there’s plenty of value to be created in the years ahead. And studying the dynamics of past technology cycles provides useful insights and patterns that give us a glimpse into how this new exciting market will shape up.

The information contained herein is based solely on the opinions of Dharmesh Thakker and nothing should be construed as investment advice. This material is provided for informational purposes, and it is not, and may not be relied on in any manner as, legal, tax or investment advice or as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy an interest in any fund or investment vehicle managed by Battery Ventures or any other Battery entity. *Denotes a Battery portfolio company. For a full list of all investments and exits, please click here.

This information covers investment and market activity, industry or sector trends, or other broad-based economic or market conditions and is for educational purposes. The anecdotal examples throughout are intended for an audience of entrepreneurs in their attempt to build their businesses and not recommendations or endorsements of any particular business.

Content obtained from third-party sources, although believed to be reliable, has not been independently verified as to its accuracy or completeness and cannot be guaranteed. Battery Ventures has no obligation to update, modify or amend the content of this post nor notify its readers in the event that any information, opinion, projection, forecast or estimate included, changes or subsequently becomes inaccurate.